HL Savings & Resilience Barometer – January 2025

Foreword

Dan Olley, Chief Executive Officer, Hargreaves Lansdown

At the start of a new year, households up and down the country will be thinking about their budgets and how they can do more with their money, while at the same time companies like HL are thinking about how we can do even more this coming year to help people to secure their financial futures.

The Hargreaves Lansdown Savings & Resilience Barometer is our tool that provides a snapshot of the nation’s financial wellbeing, tracking how resilient individuals and households are, and how that is changing over time. We see that while financial resilience has fallen from its pandemic peak it remains well above its pre-pandemic level.

Regional data paints a country of stark variation

We’re also pleased for the first time to provide a picture of the UK’s resilience area-by-area, which sadly tells a tale of a nation with stark regional variation. Pockets in and around London and the South East fare best, while the North East, North West, Scotland and Wales see some of the lowest resilience scores.

As the Government conducts a comprehensive review of pensions, it couldn’t be a more important time to assess the nation’s preparedness for their retirement, and as ever the findings in this Barometer paint a bleak picture. There has been a fall in the proportion of householders achieving adequate pension savings across all income levels, as the value of a pot required for a moderate retirement has increased 40% since 2019.

Looking regionally, this trend is sadly exacerbated, with a gap of 24% in pension adequacy between richer South East pocket and those less affluent London boroughs and North East England.

Some other highlights include:

- Wokingham and Elmbridge are the resilience capitals of the UK

- Woking boasts not only the highest resilience in the country, but also those who are most on track for retirement

- The authority with highest adequate savings is Richmond Upon Thames

- The area with the biggest savings boost since 2019 is Tower Hamlets

- Hull is the borough with the lowest financial resilience in the country, where households have an average of £65 left at the end of the month – the lowest in the country

Reasons for optimism

There are also reasons for optimism, with our own data showing an 89%[1] increase in clients under 30, including opening JISA an JSIPP accounts for children, as more people realise that starting the investing journey early and benefiting from the exponential power of compound returns over the longer term can ensure a little saved and invested now can turn into a material income in later life

The underlying detail is fascinating, and being able to see the data at this level gives a far greater level of depth. Many of the stakeholders we have engaged with over the last 4 years have agreed with the need for this next layer of details we look forward to engaging over the coming weeks and months with a wide range of stakeholders across financial services, consumer champions, think tanks, charities and of course Government and regulators about these important findings.

It is striking that as we’ve fought the challenges of the cost of living crisis, it is the longer term resilience of pension adequacy that has fallen during that period across the board. Helping households finish work with sufficient monies built up to provide for retirement is a central part of how Hargreaves Lansdown helps people to secure their financial futures.

Lastly, given the importance of comprehensive data on pensions as the Government embarks upon its review, we will be producing a deeper dive on pension adequacy in February of 2025, focussing on different ways to measure adequacy.

I am delighted to share our latest Barometer update as we continue to use this resource to inform politicians and policy makers in their decisions to support our financial resilience.

Executive summary

In this edition, the Barometer has been expanded to provide a picture of households’ financial resilience in the 363 local authorities across Great Britain. The report focuses on variations across local authorities in terms of households’ ability to mitigate an unexpected financial shock and the adequacy of their retirement savings, the latter of which has been hit in recent years due to high inflation. This pensions analysis will be expanded on in a spring report, which will explore how households’ preparedness for retirement varies based on the approach used to benchmark living standards in retirement.

The Barometer score for Great Britain has stabilised above its pre-pandemic levels, but this headline hides a poor performance in the ‘Plan for later life pillar’.

- The headline Barometer score for Great Britain sat at 60.5 in 2024 Q4 broadly unchanged over the last year, reflecting a more stable macroeconomic environment.

- While financial resilience has fallen from its pandemic peak it remains well above its pre-pandemic level of 57.0.

- This overall increase in the Barometer hides poor performance in the ‘Plan for later life’ pillar, where there has been a fall in households achieving adequate pension savings.

- This fall has been driven by high inflation increasing the pension pot required for a moderate standard of living in retirement by nearly 40%.

- The pension gap for the median household in Great Britain now stands at £31,546, four times larger than it was in 2019.

Fig. 1. How national financial resilience has changed from pre-pandemic1 to 2024 Q4

Local authorities in the “home counties” surrounding London are more financially resilient than local authorities in London and across the Midlands and Wales.

- The local authorities with the highest Barometer scores are clustered in the “home counties” surrounding London. These local authorities tend to have homeownership rates and household incomes that are significantly above the national average.

- The average rate of homeownership in the top 10 ranking local authorities―all of which surround London―is 69.4% (12.7 percentage points above the national average2) and surplus monthly income is £361 (£165 higher than the national average).

- The lowest Barometer scores are clustered in London, and in a band across the middle of the country that stretches from Wales to the East Midlands.

Fig. 2. Variation in the Barometer score across the local authorities of Great Britain in 2024 Q4

Households in London and the South West are well equipped to for an unexpected financial shock, while those in the Midlands, North East and Scotland are most precariously placed.

- Households’ ability to deal with unexpected shock varies significantly across local authorities.

- The local authorities with the highest proportion of households achieving adequacy of liquid assets are all in London, driven by high surplus incomes and wealth in the capital.

- On average, across the top 10 scoring local authorities 79.2% of households have achieved adequacy, while only 53.9% achieve this threshold in the 10 lowest scoring local authorities.

- Outside of London, local authorities in the South West perform particularly well in terms of the proportion of households achieving adequacy of liquid assets, with seven of the top 20 local authorities situated in this region.

Fig. 3. Variation in the proportion of households to have achieved resilience in “Adequacy of liquid assets” across the local authorities of Great Britain in 2024 Q4

Households in the “home counties” around London are most likely to be on track for a moderate retirement, while households in the North East and London score worst.

- The proportion of households achieving pension adequacy in the 10 best performing local authorities is twice as high as the rate seen in the 10 lowest scoring local authorities.

- Local authorities surrounding London have the highest proportions of households achieving pension adequacy. In addition, several local authorities in Yorkshire and The Humber score well, in part due to their higher proportion of public sector employment.

- On average across households in Yorkshire and The Humber the median pension gap―the gap between the pension savings households need for a moderate income in retirement and the level of pension savings they have―is £33,652. In contrast, in poor performing local authorities in London and the North East the gaps are £53,261 and £45,476, respectively.

Fig. 4. Variation in the proportion of households to have achieved resilience in “Pension value” across the local authorities of Great Britain in 2024 Q4

Local authorities across Great Britain with a higher proportion of single adult households have lower financial resilience.

- Single households have lower financial resilience as they are less able to share their living costs across earners. There is a clear relationship between the proportion of single households in a local authority and its overall financial resilience score.

- There is also variation in the headline Barometer score across city, urban and rural areas with city local authorities scoring 2.7 points lower than for rural local authorities.

Fig. 5. Local authorities with a higher proportion of single households are less resilient

The stable macroeconomic outlook is expected to leave the Barometer score largely unchanged over 2025, but an “Inflation Victory” scenario would improve households’ financial resilience in retirement.

- A relatively stable outlook for real household disposable incomes and the savings rate over 2025 leaves the Barometer score broadly unchanged. The score is forecast to sit at 60.6 in 2025 Q4, just 0.1 points above the level seen in 2024 Q4.

- In an “Inflation Victory” scenario, where bank rate falls by an additional 100 bps over 2025 boosting house price and stock market growth there would be gains in the “Plan for later life” pillar.

- This scenario would also boost the “Homeownership” and “Pension value” indicators, which are currently the weakest performing indicators in the Barometer and are set to fall by 0.6 and 1.0 points, respectively, over 2025 in the central scenario.

Fig. 6. Better financial conditions can reduce the fall in the “Pension value” and “Home ownership” indicators

Financial resilience - the current state of the nation

The headline Barometer score for Great Britain sat at 60.5 in 2024 Q4. It has remained broadly unchanged over the last year, reflecting a more stable macroeconomic environment. While financial resilience has fallen from its pandemic peak, the Barometer score continues to remain significantly above its pre-pandemic level of 57.0.

Fig. 7. How national financial resilience has changed from pre-pandemic3 to 2024 Q4

Household disposable incomes have increased in 2024 and household savings continue to remain above pre-pandemic levels.

The 2024 Q4 Barometer score has been boosted by an expected 1.9% increase in real household disposable income over 2024, driven by the strong wage growth and falling inflation seen over the first half of the year. The high savings rates seen in 2024 continue to bolster the Barometer score relative to the pre-pandemic period. Recent revisions from the Office for National Statistics have resulted in reductions in the historical savings rates in 2022 and 2023 and increased real household disposable income over this period. The net effect of these revision has reduced the “Save a penny for a rainy day” pillar score in those years.

Fig. 8. Real household disposable income improved during 2024 H1, and the savings ratio remains elevated on its 2019 level4

While the Barometer has remained above 2019 levels, recent gains in surplus incomes and cash savings have not been shared evenly and the median pension saving gap has quadrupled.

The 3.4-point increase in the headline Barometer score since 2019 has been driven by improvements in household surplus income and the amount held in cash. Over this period, the median household has seen their monthly surplus income increase from £92 in 2019 to £196 in 2024 Q4, and the number of months of essential spending covered by their liquid savings more than double from 2.6 to 5.6 months.

However, this improvement has been skewed towards middle- and higher-income households. Households earning between £51,000 and £116,000 have seen a near 30 percentage point increase in the proportion achieving adequate rainy day savings (cash savings exceeding three months of essential spending). But for households earning less than £26,000, the proportion achieving this threshold has fallen slightly since 2019.

This improvement also masks poor performance in the value of pension indicator―which tracks households’ total pension savings as a proportion of the pension value required for a moderate standard of living in retirement. This has been primarily driven by high inflation increasing the pension pot required for a moderate standard of living in retirement by nearly 40%. The pension gap for the median household is now £31,546, four times larger than it was in 2019. This has led to a significant fall in the proportion of households achieving pension-value adequacy, particularly among middle- and low-income households.

Fig. 9. Mid- to high-income households have seen the biggest improvement in the “Adequacy of liquid assets” indicator, while the “Pension value” indicator has fallen for all households5

Financial resilience across local authority districts

In previous editions of this report, the Barometer has been used to explore variations in financial resilience across the 40 NUTS2 regions of Great Britain. In recognition of the importance of understanding geographic variations at a more granular level, the Barometer framework has been expanded to cover the 363 local authorities across Great Britain. The extension has been delivered by adjusting the nationally representative dataset that underpins the Barometer to reflect the financial and demographic characteristics of each local authority. For further details on the approach, please see the updated Barometer methodology document.

The new granular local authority perspective highlights the patterns and variations in financial resilience across Great Britain.

The heatmap in Fig. 4 shows that the local authorities with the highest Barometer scores are clustered in the “home counties” surrounding London. These local authorities tend to have homeownership rates and household incomes that are significantly above the national average. Households that own their own property tend to have higher financial resilience as they are able to accumulate home equity, and they naturally tend to have higher surplus incomes and more wealth. The average rate of homeownership in the top 10 ranking local authorities―all of which surround London―is 69.4%, which is 12.7 percentage points higher than the national average.6 The median household surplus income across the top 10 ranking local authorities is £361, which is £165 higher than the national average.

The local authorities with the lowest Barometer scores are clustered in London, and in a band across the middle of the country that stretches from Wales to the East Midlands. Despite high household incomes in London, exceptionally low homeownership rates weigh on the financial resilience scores for local authorities in the region. Across local authorities in central London, the average rate of homeownership is just 30.7%, which is less than half the average rate seen in the top 10 highest performing local authorities across the nation. The poorer financial resilience in band across the middle of the country is driven by varying combinations of lower household incomes and homeownership rates.

Fig. 10. Variation in the Barometer score across the local authorities of Great Britain in 2024 Q4

A comparison between the highest and lowest scoring local authorities highlights the important role that location plays in determining a household’s financial resilience. The Barometer score for Wokingham (the highest scoring local authority) is over 13 points higher than the score in Kingston Upon Hull (the lowest scoring local authority). For comparison, this financial resilience gap is similar in magnitude to the 15-point gap between households in the third income quintile and fifth income quintile. Again, homeownership and household income are key drivers of the difference in between the highest and lowest scoring local authorities. Average homeownership rates across the top 10 local authorities are 23.7 percentage points higher than in the bottom 10 local authorities, and median household surplus income is just under 3.5 times higher.

Fig. 11. Top and bottom ranking local authority districts (LAD) by Barometer score, 2024 Q4

| Top Ranking | LAD | Overall Index | Bottom Ranking | LAD | Overall Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wokingham | 67.4 | 363 | Kingston Upon Hull | 54.1 |

| 2 | Elmbridge | 67.2 | 362 | Glasgow City | 54.2 |

| 3 | St Albans | 66.7 | 361 | Nottingham | 54.4 |

| 4 | Hart | 66.6 | 360 | Liverpool | 54.4 |

| 5 | Epsom And Ewell | 66.5 | 359 | Blaenau Gwent | 54.9 |

| 6 | Waverley | 66.3 | 358 | Blackpool | 55.1 |

| 7 | South Oxfordshire | 66.3 | 357 | Knowsley | 55.2 |

| 8 | Mole Valley | 66.2 | 356 | Stoke-On-Trent | 55.4 |

| 9 | Surrey Heath | 66.0 | 355 | Tower Hamlets | 55.5 |

| 10 | South Cambridgeshire | 65.9 | 354 | Leicester | 55.6 |

Adequacy in liquid assets

The average proportion of households with adequate liquid assets across the top scoring local authorities is 25 percentage points higher than in the bottom scoring local authorities.

Households’ ability to deal with unexpected shock varies significantly across local authorities. The local authorities with the highest proportion of households achieving adequacy of liquid assets are all in London, driven by high surplus incomes and wealth in the capital. On average, across the top 10 scoring local authorities 79.2% of households have achieved adequacy, while only 53.9% achieve this threshold in the 10 lowest scoring local authorities.

In the top scoring local authority―Richmond Upon Thames―the median household has enough liquid assets to cover over 10 months of essential spending and a monthly surplus income of £431. This is substantially above the national average of five and a half months of essential spending cover and £267 of surplus income. In contrast, in the local authority with the lowest proportion of households with adequate liquid assets―Blackpool―the median household has enough liquid assets to cover just three and a half months of essential spending and a monthly surplus income of £86.9.

Fig. 12. Top and bottom ranking local authority districts (LAD) by proportion of households to have achieved resilience in “Adequacy of liquid assets”, 2024 Q4

| Top Ranking | LAD | % of households to have achieved resilience threshold | Bottom Ranking | LAD | % of households to have achieved resilience threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Richmond Upon Thames | 83.0 | 363 | Blackpool | 52.9 |

| 2 | Wandsworth | 80.2 | 362 | Burnley | 53.7 |

| 3 | Kingston Upon Thames | 80.1 | 361 | Liverpool | 53.8 |

| 4 | City Of London | 79.2 | 360 | Kingston Upon Hull | 54.1 |

| 5 | Kensington And Chelsea | 79.0 | 359 | Hyndburn | 54.1 |

| 6 | Merton | 78.5 | 358 | Glasgow City | 54.2 |

| 7 | Harrow | 78.2 | 357 | Nottingham | 54.3 |

| 8 | Westminster | 78.1 | 356 | West Dunbartonshire | 54.4 |

| 9 | Hammersmith And Fulham | 78.1 | 355 | Knowsley | 54.5 |

| 10 | Bromley | 77.7 | 354 | Leicester | 55.1 |

Outside of London, local authorities in the South West perform particularly well in terms of the proportion of households achieving adequacy of liquid assets, with seven of the top 20 local authorities situated in this region. On average, across local authorities in the South West the median household has enough liquid assets to cover just over seven months of essential spending and a monthly surplus income of £272. In West Devon, which ranks eleventh nationally and the highest in the South West, the median household has roughly eight months of essential spending covered and a monthly surplus income of £306.

Fig. 13. Variation in the proportion of households to have achieved resilience in “Adequacy of liquid assets” across the local authorities of Great Britain in 2024 Q4

The local authorities which have seen the largest increase in the proportion of households achieving adequacy of liquid assets all have a high proportion of renters. Among the 10 local authorities that have seen the largest improvements, the average proportion of renters is 68%. This is 12 percentage points above the overall proportion of renters across Great Britain. Moreover, across the nation, the proportion of renters achieving adequacy of liquid assets has increased by 18.9 percentage points since 2019, outperforming the improvement seen by homeowners by 2.6 percentage points. This trend is the result of household disposable income growth outstripping rental price growth. However, it is important to note that while the financial resilience of renters has improved in recent years, this group still lags the national average.

Fig. 14. Top ranking local authority districts (LAD) by change in the proportion of households to have achieved resilience in “Adequacy of liquid assets”, 2019 to 2024 Q4

% of households to have achieved resilience threshold

| Top Ranking | LAD | 2019 | 2024 Q4 | Additional households 2019–2024 Q4 (ppt) | Proportion of renters7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tower Hamlets | 48.0 | 70.1 | 22.1 | 74.8% |

| 2 | Cambridge | 50.0 | 71.4 | 21.4 | 60.7% |

| 3 | Barking And Dagenham | 46.6 | 67.8 | 21.2 | 58.7% |

| 4 | City Of London | 58.1 | 79.2 | 21.1 | 70.6% |

| 5 | Westminster | 57.2 | 78.1 | 20.9 | 75.8% |

| 6 | Newham | 49.1 | 69.7 | 20.6 | 69.5% |

| 7 | Leicester | 34.6 | 55.1 | 20.5 | 58.3% |

| 8 | Islington | 52.8 | 73.1 | 20.3 | 72.9% |

| 9 | Hammersmith And Fulham | 58.1 | 78.1 | 20.0 | 69.1% |

| 10 | Hackney | 51.4 | 71.0 | 19.6 | 73.6% |

Adequacy in pension savings

The average proportion of households achieving pension adequacy in the 10 best performing local authorities is 24 percentage points higher than in the 10 lowest scoring local authorities.

The proportion of households with sufficient pension savings to achieve a moderate income in retirement varies significantly across local authorities. On average, across the 10 top scoring local authorities, the proportion of household with adequate pensions savings is 49.3% compared to 24.2% in the bottom scoring local authorities. In Wokingham―the highest scoring local authority― the median household has a positive pension gap8 of £265 which stands in sharp contrast to the £54,641 gap in Kingston Upon Hull―the lowest scoring local authority.

Fig. 15. Top and bottom ranking local authority districts (LAD) by proportion of households to have achieved resilience in “Pension value”, 2024 Q4

| Top Ranking | LAD | % of households to have achieved resilience threshold | Bottom Ranking | LAD | % of households to have achieved resilience threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wokingham | 51.2 | 363 | Kingston Upon Hull | 22.5 |

| 2 | Hart | 50.0 | 362 | Newham | 22.6 |

| 3 | St Albans | 49.6 | 361 | Barking And Dagenham | 24.6 |

| 4 | Elmbridge | 49.5 | 360 | Brent | 25.0 |

| 5 | East Renfrewshire | 49.2 | 359 | Tower Hamlets | 25.0 |

| 6 | Ribble Valley | 49.0 | 358 | Nottingham | 25.2 |

| 7 | Waverley | 48.8 | 357 | Leicester | 25.5 |

| 8 | Mole Valley | 48.6 | 356 | Sandwell | 25.7 |

| 9 | Aberdeenshire | 48.5 | 355 | Stoke-On-Trent | 25.7 |

| 10 | South Cambridgeshire | 48.4 | 354 | Hackney | 25.9 |

Local authorities surrounding London have the highest proportions of households achieving pension adequacy. In addition, several local authorities in Yorkshire and The Humber score well, in part due to the higher proportion of public sector employment, along with the South East. On average across local authorities in the South East, 40.9% of households have achieved financial pension adequacy and the median pension gap is £22,172, while 35.6% of households in Yorkshire and The Humber have achieved financial pension adequacy and have a median pension gap of £33,652. In contrast, in local authorities in London and the North East, which have particularly low levels of households achieving pension adequacy (30.7% in London and 32.3% in the North East), the median pension gaps are £53,261 and £45,476, respectively.

Fig. 16. Variation in the proportion of households to have achieved resilience in “Pension value” across the local authorities of Great Britain in 2024 Q4

City, Urban, and rural classification

Splitting local authorities into city, urban, and rural groups9 reveals that financial resilience is lowest in cities and highest in rural communities.

The average Barometer score across city local authorities is 2.7 points lower than for rural local authorities. City local authorities not only perform worse on average, but they are overrepresented in the 50 lowest scoring local authorities and underrepresented in the 50 highest scoring local authorities. City local authorities account for 26% of all local authorities in Great Britain, but over half of the 50 lowest scoring local authorities.

A key driver of lower financial resilience in cities is the high proportion of renters and single households who both score worse in “Plan for later life”. Renters also perform worse in both the “Plan for later life” as they don’t have home equity and the “Save a Penny for a rainy day” pillars due to their lower wealth and surplus income. Single households are discussed in more detail later in the report. On average, renters account for 46.1% of households in city local authorities compared with 36.4% in urban local authorities and 32.3% in rural local authorities. In city local authorities, the median pension gap is £40,107 compared to £29,757 in rural local authorities.

| Classification | Total count | Top 50 | Bottom 50 |

|---|---|---|---|

| City | 26% | 16% | 52% |

| Urban | 45% | 48% | 44% |

| Rural | 29% | 36% | 4% |

Single adult households

Local authorities across Great Britain with a higher proportion of single adult households have lower financial resilience.

Single households have lower financial resilience as they are less able to share their living costs across earners, which limits their ability to save for a rainy day and plan for their retirement. Fig. 11 shows that as the proportion of single households in a local authority increases, the financial resilience score decreases. The average Barometer score in the 10 local authorities with the lowest proportion of single households is 7.6 points higher than the average score in the 10 local authorities with the highest proportion of single households.

In Wokingham―the local authority with the lowest proportion of single households―the median household has enough liquid assets to cover over eight months of essential spending, a monthly surplus income of £382, and a pension gap of £265. In contrast, Glasgow City―the local authority with the highest proportion of single households―the median household has enough liquid assets to cover just under four months of essential spending, a monthly surplus income of £69, and a pension gap of £35,984.

Fig. 17. Local authorities with a higher proportion of single adult households have lower financial resilience

Outlook for the next 12 months

Relatively stable outlook for household disposable income and the savings rate is expected to leave household financial resilience largely unchanged over 2025.

Real disposable household income in 2025 Q4 is expected to be 0.4% higher than it was in 2024 Q4. Growth in household disposable income will be held back by an inflation forecast that is slightly above the Bank of England’s 2% target over the course of 2025 and an expected increase in the number of households in Great Britain. One key area of uncertainty in the forecast is around the impact of a shift to a more protectionist US trade policy under President Trump. Our central forecast assumes that the UK will remain outside any new US tariff regime, and British households are set to benefit from the post-election stock market rally which will have a small positive effect on the headline Barometer score.

The savings ratio is expected to fall slightly over the forecast from 8.4% in 2024 Q4 to 8.1% in 2025 Q4. This decrease will put some downward pressure on the overall Barometer score. However, the savings rate remains significantly above the levels seen in 2019, meaning overall financial resilience in 2025 will continue to remain substantially above the levels seen in 2019.

Fig. 18. Real disposable income growth is expected to remain stable, and savings elevated

A relatively stable outlook for real household disposable incomes and the savings rate over 2025 leaves the Barometer score broadly unchanged. The score is forecast to sit at 60.6 in 2025 Q4, just 0.1 points above the level seen in 2024 Q4.

In 2025 Q4, the “Save a penny for a rainy day” score is expected to be 1.2 points higher than in 2024 Q4. Within this pillar, median household surplus income is expected to sit at £204 in 2025 Q4, up by £8 on the level seen in 2024 Q4. The wealthiest are expected to continue to outperform the average. Indeed, in the “Save a penny for a rainy day” pillar, those in the fourth and fifth household income quartiles score 16.7 and 22.9 points more, respectively, than the average of 72.2.

Fig. 19. Overall financial resilience is expected to remain elevated

The central forecast assumes there will be 100 bps of cuts next year, leaving the Bank Rate at 3.75% by the end of 2025. Inflation is expected to remain slightly above target across 2025 due to rising energy costs, persistent core CPI inflation, and increased demand from the policy announcements at Autumn Budget. However, if inflation were to ease sooner and the potential inflationary risks abate10, this could enable central banks to cut interest rates significantly, boosting financial markets, global economic growth, and households’ financial resilience. In this “Inflation Victory” scenario, the bank rate falls by an additional 110 bps over 2025 and house price and stock market growth are 0.4 and 7.6 percentage points stronger, respectively.

Fig. 20. Lower interest rates and faster economic growth boost house prices and the financial markets

The “Inflation Victory” scenario would lead to gains in the “Plan for later life” pillar. It would also boost the “Homeownership”11 and “Pension value” indicators, which are currently the weakest performing indicators in the Barometer and are set to fall by 0.6 and 1.0 points, respectively, over 2025 in the central scenario. The “Inflation Victory” scenario would reduce the expected fall in both indicator scores by around a third, and increase the proportion of households achieving pension adequacy in 2025 Q4 by 0.3 percentage points and decrease the median pension gap by £252.

Fig. 21. Better financial conditions can reduce the fall in the “Pension value” and “Home ownership” indicators

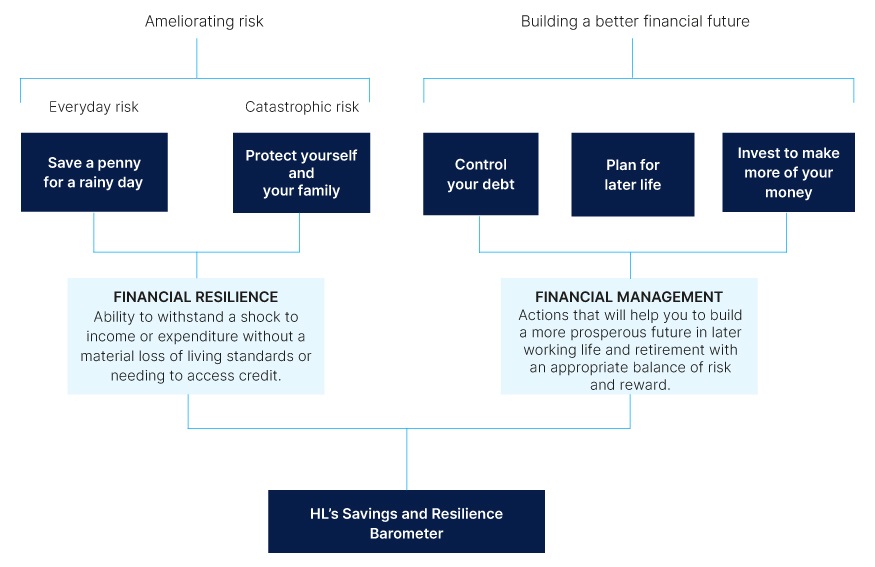

About the barometer

The savings and financial resilience barometer is an index measure designed and produced by Oxford Economics. It is based around Hargreaves Lansdown’s five building blocks for financial resilience depicted in Fig. 29. The aim of the barometer is to provide a holistic measure of the state of the nation’s finances, monitoring to what extent households are prudently balancing current and future demands whilst guarding against alternative types of risk.

Fig. 22. Savings and Resilience Barometer: conceptual structure

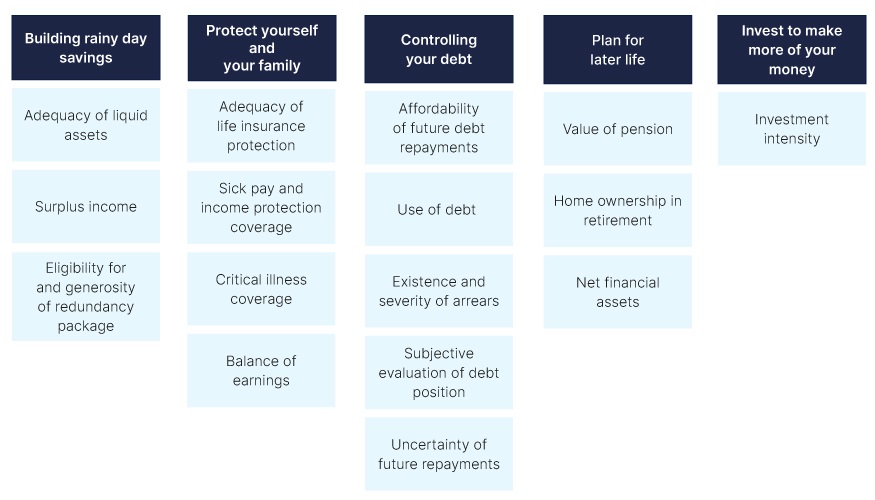

In collaboration with Hargreaves Lansdown, Oxford Economics mapped each of these pillars to a list of 16 individual indicators (Fig. 30). The data underpinning the indicators were sourced from a household panel dataset for a representative group of British households developed by linking together official datasets. The Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS), published by the ONS, was used as the core dataset due to the breadth of financial data available in the survey. This source does not include every variable required to measure the factors and the latest survey only extends as far as 2020 Q1. Therefore, we have used a range of methods including econometric analysis to build upon the core dataset using data from the Financial Lives Survey (FLS), Living Costs and Food Survey (LCFS), and the Labour Force Survey (LFS).

For each indicator, the data were used to create an index value on a scale of between zero and 100 for households in the panel. In each case, a score of 100 was assigned to households who had reached a specified resilience threshold, e.g., holding liquid assets equivalent to at least three months of essential expenditure. Households whose savings are sufficient to cover more than three months of spending are, therefore, not rewarded for this additional level of security. Such a design is appropriate to capture the concept of resilience and the intrinsic trade-offs involved in financial management. Threshold values are defined with reference to benchmark recommendations where available and, where not, using the statistical distribution of values within the dataset and the judgement of the research working group.

Fig. 23. Savings and Resilience Barometer: Barometer Indicators

To bring the dataset up to date, values were extrapolated through to 2024 Q2 using a wide range of macroeconomic and survey data and different modelling techniques. A much more detailed description of the approach can be found in the methodology report available on the project’s landing page.12 Finally, current and future values are projected based on Oxford Economics’ baseline forecast for the UK economy from its Global Economic Model (GEM).

Methodology changes

For the January 2025 edition, we have enhanced the framework to estimate financial resilience at the local authority level. Our nationally representative financial resilience dataset is adjusted to reflect the financial and demographic characteristics of each local authority in Great Britain. This is then used to estimate each local authorities’ overall financial resilience at the overall barometer, pillar and indicator level, the findings are also available for different demographic splits within each local authority. An overview of the methodology is found below with more details included in the methodology document.

Modelling households at the local authority level

For each of the 10,000 households in our dataset, the likelihood of residing in a specific local authority is calculated based on its wealth distribution and demographic composition. This data is then used to estimate indicator scores for each local authority and different demographic splits within each local authority.

The distribution of wealth across each local authority is based on sophisticated neutral network models. We combine information on wealth holdings from three core datasets: the Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS), the 2021 Census, and the Land Registry’s Price Paid datasets. Together, these datasets form part of an eco-system that allows us to generate estimates of the variation in household wealth across England, Wales, and Scotland at the local authority level. The wealth variables modelled include property and land, physical, financial and pension wealth which collectively comprise total household wealth. Non-wealth distributional data from the Census, such as age, tenure and socio-economic status, are also used to ensure the household specific local authority weights reflects the proportions from this dataset.

Banding categorisation

To aid the communication of the barometer results, we have designed a method to allocate households between five bands according to their barometer scores. These bands are labelled as: very poor, poor, fair, good, and great. We will use the share of households in each band as a reference point to communicate the changing state of financial resilience in the UK.

The bands are primarily based on the quintile distribution of pre-pandemic barometer scores. The pre-pandemic distribution of “Control your debt”, “Invest to make more of your money” and to a lesser extent “Protect Yourself and Your Family” have been adjusted to take account of the nonlinear distribution of scores. Threshold scores for each band are fixed to values observed in the pre-pandemic (2019) period so that changes in the shares can be used to trace developments over time.

Fig. 24. Score range and pre-pandemic (2018 Q1–2020 Q1) proportion of households

Score range

| Band | Save a penny for a rainy day | Protect yourself and your family | Control your debt | Plan for later life | Invest | Overall Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very poor | 0-28 | 0-42 | 0-54 | 0-5 | 0 | 0-42 |

| Poor | 28-50 | 42-66 | 52-66 | 5-31 | 1-19 | 42-54 |

| Fair | 50-71 | 66-71 | 66-78 | 31-52 | 19-52 | 54-63 |

| Good | 71-89 | 76-88 | 78-95 | 55-75 | 52-82 | 63-72 |

| Great | 89-100 | 88-100 | 95-100 | 75-100 | 82-100 | 72-100 |

Pre-pandemic proportion of households

| Band | Save a penny for a rainy day | Protect yourself and your family | Control your debt | Plan for later life | Invest | Overall Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very poor | 22 | 19 | 19 | 20 | 52 | 20 |

| Poor | 20 | 15 | 19 | 20 | 13 | 20 |

| Fair | 20 | 26 | 19 | 20 | 12 | 20 |

| Good | 20 | 20 | 19 | 27 | 12 | 20 |

| Great | 20 | 20 | 24 | 13 | 12 | 20 |

About Oxford Economics

Oxford Economics was founded in 1981 as a commercial venture with Oxford University’s business college to provide economic forecasting and modelling to UK companies and financial institutions expanding abroad. Since then, we have become one of the world’s foremost independent global advisory firms, providing reports, forecasts and analytical tools on more than 200 countries, 100 industries, and 7,000 cities and regions. Our best-in-class global economic and industry models and analytical tools give us an unparalleled ability to forecast external market trends and assess their economic, social and business impact.

Headquartered in Oxford, England, with regional centres in New York, London, Frankfurt, and Singapore, Oxford Economics has offices across the globe in Belfast, Boston, Cape Town, Chicago, Dubai, Dublin, Hong Kong, Los Angeles, Mexico City, Milan, Paris, Philadelphia, Stockholm, Sydney, Tokyo, and Toronto. We employ 450 staff, including more than 300 professional economists, industry experts, and business editors—one of the largest teams of macroeconomists and thought leadership specialists. Our global team is highly skilled in a full range of research techniques and thought leadership capabilities from econometric modelling, scenario framing, and economic impact analysis to market surveys, case studies, expert panels, and web analytics.

Oxford Economics is a key adviser to corporate, financial and government decision-makers and thought leaders. Our worldwide client base now comprises over 2,000 international organisations, including leading multinational companies and financial institutions; key government bodies and trade associations; and top universities, consultancies, and think tanks.

January 2025

All data shown in tables and charts are Oxford Economics’ own data, except where otherwise stated and cited in footnotes, and are copyright © Oxford Economics Ltd.

The modelling and results presented here are based on information provided by third parties, upon which Oxford Economics has relied in producing its report and forecasts in good faith. Any subsequent revision or update of those data will affect the assessments and projections shown.

To discuss the report further please contact:

Henry Worthington:hworthington@oxfordeconomics.com

Oxford Economics

4 Millbank, London SW1P 3JA, UK

Tel: +44 203 910 8061

1 Pre-pandemic data based on the seventh wave of the Wealth and Asset Survey from 2018 Q2 to 2020 Q1.

2 Ownership rates are based on households with occupants under 65, as published in the census, to align with the Financial Resilience Barometer, which excludes retired households.

3 Pre-pandemic data based on the seventh wave of the Wealth and Asset Survey from 2018 Q2 to 2020 Q1.

4 Savings ratio calculated as household disposable income minus household consumption divided by household disposable income. This may differ from other measures of savings ratios, which can include non-household specific indicators.

5 Income bands based on the seventh wave of the Wealth and Asset Survey from 2018 Q2 to 2020 Q1 and up-rated based on earnings growth between 2019 and 2024.

6 Ownership rates are based on households with occupants under 65, as published in the census, to align with the Financial Resilience Barometer, which excludes retired households.

7 Proportion of renters based on tenure of aged 16_64, census 2021.

8 The gap between the pension savings households needs for a moderate income in retirement and their current level of pension savings. A positive pension gap means that the household has pension savings above the savings threshold needed to achieve pension adequacy.

9 England based on the ONS classification of rural and urban local Authorities. City is based on Urban with Major Conurbation and Urban with Minor Conurbation. Urban is based on Urban with City and Town and Urban with Significant Rural. Rural is based on Mainly Rural and Largely Rural. Wales is based on the “Rural Wales” classification. City is based on Urban authorities. Urban authorities is based on Other authorities. Rural is based on Valleys and rural authorities. Scotland is based on the Scottish government's urban-rural classification. It is classified based on the population proportion living in urban, town and rural areas with the classification based on the largest proportion in the groups.

10 This scenario also includes geopolitical stabilisation and a fall in oil prices.

11 The “Homeownership” indicator captures the value of home equity held by households.

12 https://www.hl.co.uk/features/5-to-thrive/savings-and-resilience-comparison-tool.