Demographic trends are a major topic for financial markets. It’s a multi-decade shift that will impact emerging markets and developed markets alike.

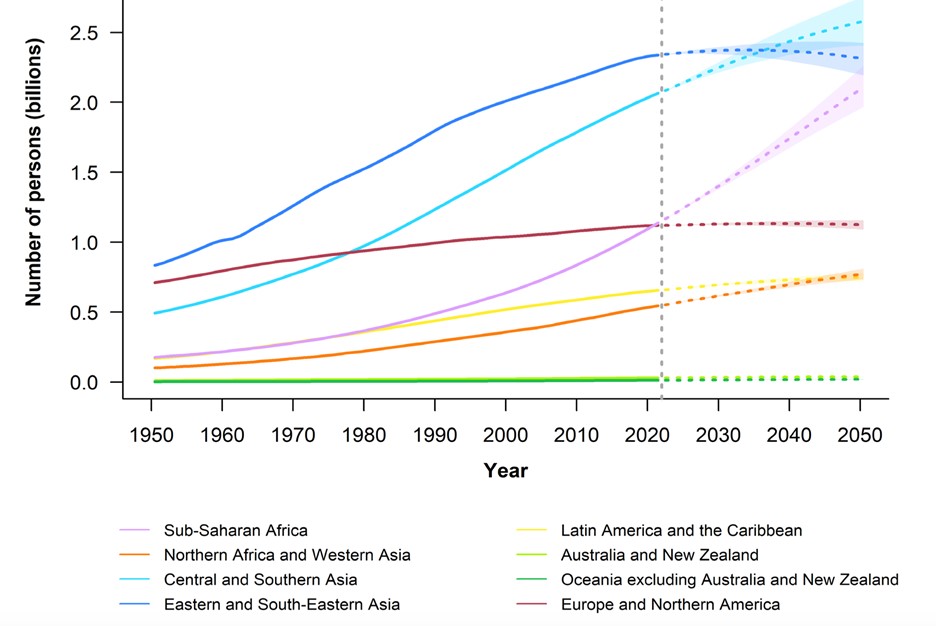

While the rate of population expansion differs across the world, the overall rate of growth is slowing – the UN think the world’s population could peak in the mid-2080s, at 10.4 billion people.

However, the population growth won’t be even, while some countries in sub-Saharan Africa will see their populations swell, other countries like Italy, Germany and Japan will see their populations age dramatically.

The World Health Organisation is expecting the number of over-60s to double by 2050 to 2.1 billion people globally. It also thinks the number of over-80s will triple to reach 426 million people in the same time frame.

The economic sweet spot turns sour

For most of the last 30 years, the effective global labour supply has grown continuously, because of three things.

Firstly, the re-integration of the Eastern European workforce after the collapse of the USSR. Secondly, the rise of China and its inclusion in the World Trade Organisation in 1997, which more than doubled the amount of global labour. The third factor was benign demographic trends in most advanced economies. These factors combined meant that the effective global labour supply rate doubled between 1991 and 2018.

These three factors created an economic sweet spot that led to low levels of inflation, low interest rates and near constant growth. Up until the financial crisis in 2008 that is. But, while stable inflation levels and near constant growth rates are good for society, the demographic changes had one unescapable effect – the large positive supply shock to the global labour force led to a stagnation in real wages, especially in unskilled and semi-skilled labour in advanced economies.

Towards the end of the last decade, disgruntled workers started to make their voices heard at the ballot box. This led to a surge in political populism, which had large implications for the global economy and global trade.

So, when we look at the demographic trends of the past, they came with both benefits and drawbacks, and it’s important not to sugar-coat them. Likewise, the demographic change that’s happening now, will have both positive and negative impacts on the global economy.

Healthcare and demographic change

The issue with an ageing population is it requires large amounts of care and resources to be directed to look after the elderly.

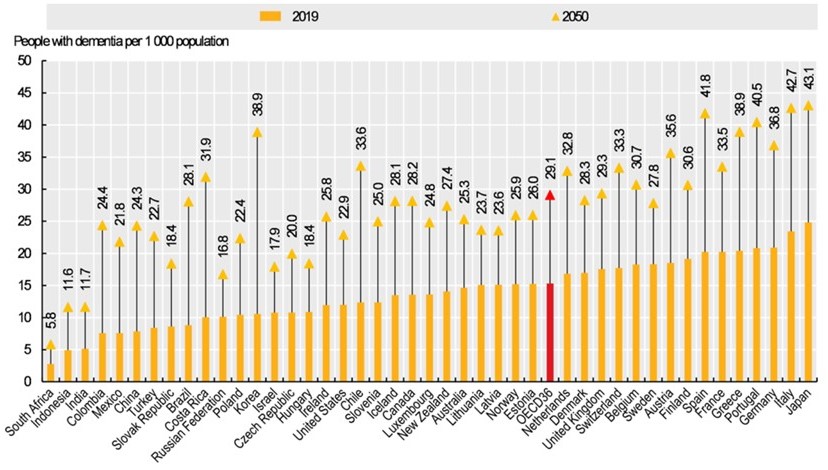

The chart below shows one of the most important and devastating trends for ageing populations – the growing prevalence of dementia.

Estimated prevalence of dementia from 2019- 2050

Source: OECD and UN.

Dementia rates are expected to increase around the world in the coming decades. Its prevalence is expected to be most pronounced in Japan, with 43.1 incidences per 1000 population by 2050. Italy and Germany aren’t far behind. In the UK, the rate of dementia per 1,000 population is expected to be 29.3 by 2050, just above the OECD average of 29.1.

How to manage ageing populations will differ across the world as differences across countries and regions, along with social and cultural preferences will determine the future for older people. Although pharmaceutical companies are actively looking at ways to treat dementia, so far there’s been no definitive treatment.

Demographic trends of the future

The other major demographic shift is that India will likely overtake China as the most populated country at some point in 2023. China experienced a drop in its population in 2022, for the first time since 1961. As China’s population ages, it’s also dealing with the same problems as advanced economies like Italy and Germany, which could include a permanent slowdown in its growth rate.

In contrast, India and the other fast-growing nations in Africa and south Asia will likely become more important to the global economy as they see an increase in their working age population.

Global population size and annual growth rates

Source: UN, 2022.

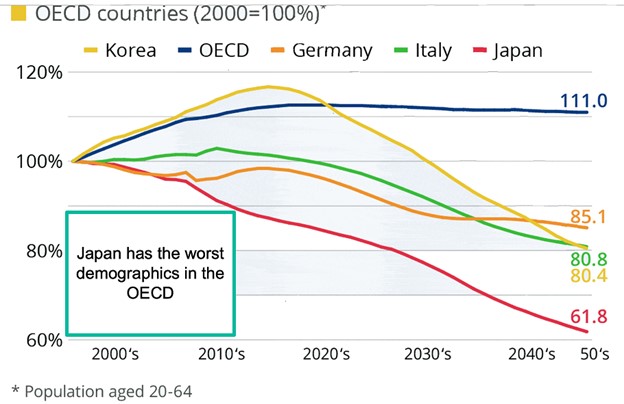

One of the most interesting features of the future trends for working age populations is where growth is expected, and where the proportion of working age people are expected to decline.

The chart below shows two interesting developments. Firstly, for the OECD in total, the size of the working age population is expected to increase to 111% of the 2000 figure by 2050. This growth is driven by countries with strong birth rates and large populations like Turkey and the US. This is positive for the future growth outlook.

OECD countries – working age populations

However, the balance of growth is likely to shift. Some western and developed Asian countries like Japan, Korea, Germany, and Italy are expected to see a sharp decline in their working age populations in the coming decades.

While Japan’s working age population has been declining since the 1990s, this shift only happened in Korea in 2019. The OECD expects that Japan’s working age population will only be 60% of its current size by 2050. For Korea and Italy, their working age populations size will be 80% of their current rates.

The impact of this decline in working age population is complex. For example, growth should slow, underfunded social care systems will be a major issue, along with tight labour markets and overstretched medical services.

The economic impacts of demographic change

The key impact for investors is that corporate profits could be curtailed by ageing populations. Advanced economies are most at risk from ageing populations, yet they have the lion’s share of corporate activity and capital.

Higher inflation could lead to higher interest rates, especially in the western world. To add to this, higher debt levels will also be needed to fund medical costs and social care. Higher debt levels in countries as varied as the UK and China could lead to sovereign rating downgrades, and lower levels of investment, both domestically and abroad, in the future.

What’s next for inflation in 2023?

A more fragile financial future

The debt levels of corporations, especially in China, could also be impacted by changing demographics.

In recent years, China’s high growth rates have led to a massive increase in debt to finance investments, especially in the real estate sector. A permanently higher interest rate environment could make new investments harder to fund in future, and it could weigh on growth. Default rates on previous investments could also rise.

This shows how an ageing population could go some way to making the global financial system more fragile.

Tight labour markets have been a feature of the post-pandemic economy in the US and the UK. This has, in part, been caused by a shrinking labour force. As labour becomes scarcer, wages will naturally rise. The positive impact of this is that inequality should fall, and perhaps this will tame the surge in populist politics in the future?

We’ll have to wait and see whether this will encourage the flow of labour from countries where the labour force is growing, like India and Africa, to countries where it’s shrinking and the number of elderly is rising.

These demographic forces will change the fabric of society in both advanced and less developed economies in the coming decades. As we move through the 2020s, these trends are less theoretical and are impacting our real economies. While there are reasons to be optimistic about economic change, it also comes with challenges.

What’s next for stock markets in 2023?

Kathleen Brooks is Founder of Minerva Analysis, a market analysis company. Hargreaves Lansdown may not share the views of the author.